Iran’s Nuclear Programme: Compliance and Escalation

For a decade, Iran’s nuclear activities have embodied a paradox of earnest cooperation and alarming provocation throughout the Middle East. On one hand, Tehran adhered closely to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) after its signing in 2015. International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors confirmed “Tehran’s strict compliance with its commitments” under the deal in the ensuing years. By early 2016, Iran had shipped abroad enriched uranium, dismantled centrifuges, and allowed intrusive inspections; the UN and major powers responded by lifting nuclear-related sanctions. Every quarterly IAEA report up to 2018 found Iran respecting the accord’s limits – enriching uranium only to the low 3.67% purity permitted, capping stockpiles, and granting inspectors broad access (armscontrol.org). Yet this record of compliance was disrupted in May 2018 when U.S. President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew from the JCPOA and reimposed sanctions. Iranian officials initially stayed patient, urging the deal’s European guarantors to offset Washington’s breach. Only when alternative arrangements failed did Iran begin to step beyond the JCPOA’s limits in 2019, resuming higher-level uranium enrichment after a year of continued full compliance (iris-france.org).

- Iran’s Nuclear Programme: Compliance and Escalation

- Regional Ambitions and Proxy Warfare

- Iranian Terrorist Funding

- The Erosion of International Law and the ‘Might Is Right’ Era

- Diplomacy on the Brink – and the Case for Dialogue

- The United States: Maximum Pressure and Repercussions

- Saudi Arabia: A Rivalry at the Forefront

- Qatar: Mediation from the Middle Ground

- Israel: An Unyielding Adversary

- Russia and China: Hesitant Giants in the Fray

- BA Conclusion: Increasingly Complexity Requires Nuance

Today, Iran’s nuclear programme has advanced in troubling ways even as Tehran insists its aims remain peaceful. In response to the collapse of the JCPOA’s economic benefits, Iran gradually expanded its enrichment of uranium to levels far beyond the deal’s cap. According to IAEA reports, Iran now possesses roughly five tonnes of uranium enriched above 20%, including an estimated 400 kg enriched to 60% (iris-france.org). These quantities and purities remain short of weapons-grade (90%) material, but they mark a dramatic departure from the deal’s constraints. Western officials were particularly alarmed in early 2023 when inspectors detected particles of uranium enriched to 83.7% at Iran’s Fordow facility – a level only a short technical step from bomb fuel (cfr.org). Iranian authorities downplayed the finding as an unintended byproduct of routine work. Crucially, experts assess that Iran has not yet made the political decision to proceed to actual weapons-grade enrichment. As things stand, Tehran would still need many months (at least a year, by most estimates) to produce and weaponize nuclear material for a bomb after any such decision. This built-in timeframe offers a slim diplomatic window – a reminder that however tense the situation, Iran’s nuclear advance is not unrestrained. It is therefore simultaneously true that Iran once painstakingly complied with nuclear limits and that it is now inching closer to nuclear-weapons capability. Any nuanced analysis of the Iranian programme must acknowledge both realities. The challenge for the international community is to address Iran’s recent escalations without losing sight of the trust previously built through agreements. In an era when facts on the ground shift quickly, these contradictory truths underline the complexity of judging Iran’s intentions and the difficulty of crafting an effective response.

Regional Ambitions and Proxy Warfare

Parallel to its nuclear endeavours, Iran’s regional behavior presents another dual narrative. The Islamic Republic portrays itself as a status-quo power honoring international covenants, yet it also unabashedly projects influence via ideological and military proxies across the Middle East. Indeed, support for non-state militant actors has been a pillar of Iranian foreign policy since 1979. Tehran’s revolutionary leadership has long cultivated a network of armed partners – often styled as the “Axis of Resistance” – to extend its reach and counter its adversaries. These groups, ranging from well-organized militias to political movements, operate in multiple countries and have for years conducted attacks against Iran’s foes, including U.S. and Israeli interests. Iran’s motivations are rooted in both ideology and hard security: it champions itself as defender of Shia Muslim communities and other “oppressed” peoples (notably the Palestinians), even as it seeks strategic depth to deter hostile powers. By backing militias abroad, Tehran compensates for its own conventional military limitations and establishes forward positions to dissuade enemies from attacking Iran itself. This asymmetric “forward defence” strategy allows Iran a degree of deniability (however implausible) for its proxies’ actions, while still reaping the benefits of their battlefield leverage (sgp.fas.org).

In practice, Iran’s proxy network sprawls across the Levant, Mesopotamia, and the Arabian Peninsula. The Lebanese Hezbollah stands out as the most powerful Iranian-aligned militia, effectively a parallel army in Lebanon and a longtime foe of Israel. Born during Lebanon’s civil war with Iranian guidance, Hezbollah today receives the bulk of its weaponry, training, and funding from Tehran. It has served as Iran’s spearpoint against Israel – exemplified by the 2006 Israel–Hezbollah war – and more recently has assisted pro-Iran allies in Syria’s conflict. In Gaza and the West Bank, Palestinian factions such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad have likewise benefited from Iranian arms and cash over decades (sgp.fas.org). The U.S. State Department estimates Iran provides up to $100 million annually in support to Palestinian militant groups including Hamas. Tehran’s ties to Sunni Islamists may seem purely tactical, but they serve a broader aim of positioning Iran as a champion of the Palestinian cause across the Muslim world. Further east, in Iraq and Syria, Iran has cultivated a constellation of predominantly Shia militias – from Iraq’s Kata’ib Hezbollah and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq to Afghanistan-origin “Fatemiyoun” brigades – some of which were mobilized to fight the Islamic State and later entrench Iranian influence in Baghdad and Damascus. In Yemen, Iran’s support for the Houthi movement (Ansar Allah) since the 2010s transformed a local rebellion into a regional flashpoint. Iranian-supplied missiles and drones have enabled the Houthis to strike targets deep in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, escalating a conflict that directly challenges Riyadh’s security. Even as far afield as Bahrain, Iranian meddling with Shia opposition groups has been periodically alleged, feeding Gulf Arab suspicions of Tehran’s hegemonic aspirations.

It is true that Iran’s proxy interventions have often been destabilizing – exacerbating wars in Syria and Yemen, and entrenching militant power at the expense of weak states. Iranian-armed factions have sometimes drawn their home countries into Iran’s fights; for example, Hezbollah’s deep involvement in the Syrian civil war propped up the Assad regime but helped spark a refugee crisis and new Israeli strikes in Syria. Iranian proxies have also targeted Western forces: in late 2023 and early 2024, as regional tensions spiked, Iran-backed militias in Iraq and Syria launched dozens of rocket and drone attacks on U.S. bases, killing American personnel (cbsnews.com). Yet it is also true that these militias are integral to Iran’s security doctrine and self-perception. From Tehran’s perspective, groups like Hezbollah and the Houthis are not mere pawns to sow chaos, but rather vital partners ensuring that Iran itself never faces isolation or invasion. For years, the threat of Hezbollah’s rocket arsenal was seen as deterring Israel from striking Iran’s nuclear sites. Likewise, by bleeding Saudi Arabia in Yemen, the Houthis have given Tehran leverage against a regional rival. The recent conflicts have tested this strategy: the 2023 Hamas-Israel war and its spillover saw Iran’s allies launching missiles and drones toward Israel (from Lebanon, Yemen, and Iraq), but with limited effect on Israel’s military campaign (understandingwar.org). If anything, Israel’s forceful response severely degraded some of these proxy forces (understandingwar.org). Iran’s web of alliances is now strained, its proxies partly exhausted by years of war. Still, the fundamental point remains – Iran’s past and present actions in the region, from empowering militias to intermittent cooperation on diplomacy, reflect a complex interplay of aggression and security calculus. Tehran can at once be a deal-maker and a mischief-maker. Appreciating that duality is essential for outsiders hoping to calm the region’s fires.

Iranian Terrorist Funding

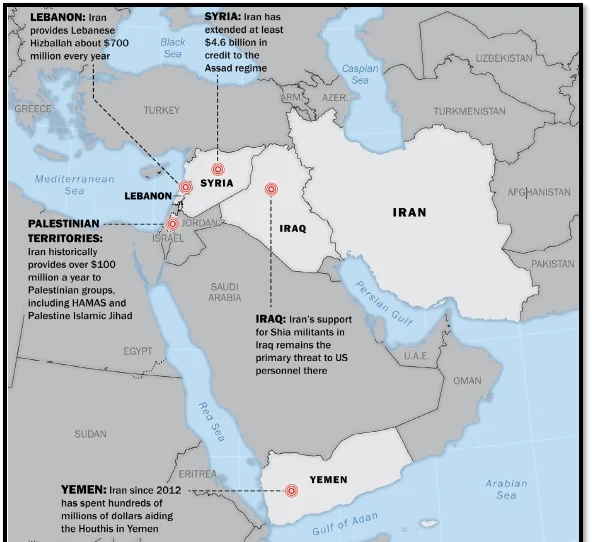

Map of the Middle East highlighting countries where notable Iran-backed groups operate (Iran’s proxy network circa 2020). Iran’s Revolutionary Guard has armed and financed militias or political movements in at least six countries, from Hezbollah in Lebanon and Syria to armed factions in Iraq, Bahrain, and Yemen.

The Erosion of International Law and the ‘Might Is Right’ Era

Iran’s nuclear and regional saga is unfolding against a disturbing backdrop: a broader decline in respect for international law and a global tilt towards raw power politics. Around the world – and acutely in the Middle East – the principles of the post-1945 world order are being eroded by the practice of might making right. The signs are unmistakable. Russia’s blatant invasion of Ukraine in 2022, in defiance of the UN Charter, was a stark example of a powerful state flouting international law. In the Middle East, too, norms long taken for granted have withered. Military interventions and occupations without international mandate, targeted killings on foreign soil, collective punishments of civilian populations – actions once widely condemned are now met with shrugs or cynical justifications. A journalist writing in June 2025 observed that we are “living in an increasingly lawless, shadowy world – where international conventions and institutions are not just ignored, but actively undermined” by states pursuing ruthless agendas. The trend spans East and West: the same piece lambasted everything from Russia’s Ukraine war and “Israel’s genocide of Palestinians” in Gaza, to the United States’ repeated use of unilateral force, as evidence that the post–World War II global order is under assault. With each such episode, political trust crumbles and hypocrisy abounds – major powers condemn rivals’ crimes while excusing their own transgressions. The cumulative effect is profoundly dangerous: it signals to strong states and non-state actors alike that “the rule of law no longer matters, that might is right, and anything goes” (eurasiareview.com).

Nowhere is this nihilistic trend more visible than in the Middle East’s current conflicts. In mid-2025, the Israeli government – facing what it deemed an existential nuclear threat – launched surprise air strikes deep into Iran. Jerusalem claimed “self-defence”; yet by all traditional legal standards, this was a preventive war rather than a response to an imminent attack. Israeli warplanes pounded sites across Iran in a campaign executed without UN authorization and in breach of the basic prohibition on force in international relations (americamagazine.org). The strikes killed combatants and civilians alike. Rather than condemn the operation, many Western leaders offered at least tacit support, echoing Israel’s framing of necessity. In France, President Emmanuel Macron went so far as to endorse Israel’s right to act and even suggested France might join operations to defend Israel if Iran retaliated. An observer from the IRIS think tank noted the “thoroughly Orwellian” inversion at play: “the aggressor becomes the victim” in the narrative, and the aggressor “must be defended” by international society. This, the commentator wrote, amounted to “a clear endorsement of the law of the strongest” and an explicit break with the principles that are supposed to govern international relations (iris-france.org). When such logic prevails – whether in Gaza, Tehran, Kyiv, or elsewhere – it hammers the final nails into the coffin of the old rules-based order. Indeed, many analysts now speak of the Middle East as entering a post-law era. The UN Security Council, paralyzed by great-power divisions, has been largely impotent in the face of recent wars. During the Gaza war of 2023–24, as tens of thousands of Palestinian civilians were killed and entire cities leveled, no binding resolution could pass to halt the fighting (carnegieendowment.org). Wartime conventions on protecting non-combatants were routinely flouted, with little consequence except outrage in the global South.

For Iran, which has always been hyper-attuned to questions of sovereignty and legal rights, this degeneration of international norms carries a mix of danger and vindication. On one hand, Tehran sees double standards everywhere. Iranian leaders ask why Israel’s undeclared nuclear arsenal is tolerated, while Iran’s nuclear energy programme (with no bomb to date) triggers talk of war. They watch Western powers ignore UN rules when it suits them – as in the 2003 Iraq invasion or the recent strikes on Iran – and conclude that power, not law, guarantees regime survival. This reinforces hardliners’ arguments that Iran would be foolish to trust Western promises or rely on international law for protection. On the other hand, the ‘might is right’ era validates Iran’s own defiance. If great powers pick and choose when to follow rules, Iran can do the same. The result is a vicious cycle: normative restraints falter across the board. As the Deputy Director of IRIS summed up, a “slow disintegration… is gripping the planet” as we collectively decide what future we want – “the law of the strongest versus a revival of… international law.” (iris-france.org) The Middle East’s fate, and the safety of millions, will depend on which of these paths the world chooses in the coming years.

Diplomacy on the Brink – and the Case for Dialogue

In this climate, the prospects for diplomacy in the Middle East appear dim, yet the need for it has never been greater. The collapse of trust and the triumph of hawks on all sides have made negotiated compromise exceedingly difficult for now. Mutual suspicion between Washington and Tehran is at an all-time high; key regional players like Riyadh and Tel Aviv see little incentive for conciliation when military leverage seems to yield quicker results. It is therefore unsurprising that formal talks have ground to a halt. Efforts to revive the Iran nuclear deal have faltered despite intermittent glimmers of hope. Starting in 2021, the remaining JCPOA signatories and the U.S. (under President Biden) engaged in on-again, off-again negotiations to restore the accord. Those talks stumbled over maximalist demands and external shocks – the election of a hardline Iranian president (Ebrahim Raisi), Russia’s war in Ukraine, and Iran’s own regional entanglements. By late 2023, whatever tentative progress made was overshadowed by new flashpoints: Iran’s military support for Russia and for groups like Hamas brought additional Western sanctions, while impending JCPOA expiry dates spurred the U.S. and Europe to extend arms embargoes on Iran unilaterally. Diplomacy limped on in European capitals and Gulf backchannels but yielded no breakthrough. As of mid-2025, officials privately concede that further Iranian nuclear advances could soon make returning to the original JCPOA impossible (cfr.org).

The region’s hot wars have likewise displaced peace talks. The Israeli-Palestinian peace process is moribund, buried under the weight of recent violence. In Syria, desultory UN-sponsored talks have produced no real reconciliation, even as outside powers quietly rehabilitate the Assad regime for lack of alternatives. Yemen’s conflict had seen a hopeful ceasefire in 2022, but a full peace deal remains elusive and could unravel under wider Iran–Saudi tensions. Meanwhile, the dramatic Israel-Iran military escalations of 2024–25 effectively closed off direct channels between those arch-foes. Rare meetings in Oman that once allowed U.S. and Iranian emissaries to converse in the shadows have been suspended amid the drumbeat of war. An illustrative incident came in June 2025: just as a sixth round of informal U.S.-Iran talks was slated in Muscat, Israel’s strikes on Iran short-circuited the gathering entirely. A parallel Franco-Saudi diplomatic initiative at the UN (which ambitiously floated recognizing a Palestinian state to defuse regional anger) was likewise stillborn in the face of Israeli intransigence and escalating combat. Hardliners in multiple capitals clearly prefer force to negotiation at present – Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu openly proclaims his belief in military solutions over “weak” diplomacy, boasting of being at war on numerous fronts. In Tehran too, voices counseling patience or compromise have been sidelined by the Revolutionary Guard faction, which argues that the West only respects strength. The current environment is thus exceptionally hostile to peacemaking (iris-france.org).

And yet, even as diplomacy stands on the brink, a path for negotiation must always exist. This is a lesson painfully learned from past Middle East conflagrations – eventually, the combatants exhaust themselves and return to talk around a table. Acknowledging that reality, some regional actors have kept diplomatic channels ajar. The Sultanate of Oman and the State of Qatar, for instance, have continued their quiet facilitation roles. Muscat has long been the venue for U.S.-Iran dialogues and still nurtures contacts with both sides. Doha, for its part, leveraged its unique position (friendly with Washington, Tehran, and groups like Hamas) to broker several short ceasefires in late 2023’s Gaza war (nav.edu, eiu.com.) Those humanitarian pauses, while fleeting, saved lives and proved that dialogue was possible even amid flames. Similarly, Saudi Arabia’s rapprochement with Iran in 2023 – mediated by China – showed that adversaries can find mutual interest in de-escalation. Riyadh and Tehran re-established diplomatic ties after seven bitter years, cooling one front in the region (atlanticcouncil.org). Although this détente is fragile (and indeed Saudi-Iranian relations have since been tested by the new Israel-Iran hostilities), the principle of negotiation was upheld. No conflict is so intractable that diplomacy cannot at least outline an off-ramp. Even Western and Iranian officials, for all their fiery rhetoric, quietly concede that they will eventually need to talk. As one seasoned British expat in the Gulf observed wryly, “War is not sustainable for any of us here – it’s bad for business, bad for everyone. So sooner or later, they’ll have to sit down and sort something out.” This pragmatic perspective – common among expatriates who prize regional stability – underscores why the door to diplomacy must never be locked permanently. The present moment offers precious little room for compromise; positions are maximalist and the wounds of recent violence are raw. But history teaches that today’s “impossible” negotiations can become tomorrow’s imperative. However bleak the horizon, statesmanship requires keeping principles of dialogue alive so that when tempers cool, there is a basis to begin rebuilding peace.

The United States: Maximum Pressure and Repercussions

No outside power has influenced Iran’s trajectory – both nuclear and regional – more than the United States. Washington’s role has oscillated between engagement and antagonism, with profound consequences for the Middle East. In the 2010s, the U.S. was a chief architect of the JCPOA nuclear agreement, reflecting a strategy of negotiated restraint. But that approach was dramatically reversed under Donald Trump’s presidency. Trump condemned the JCPOA as “the worst deal ever” and, in 2018, withdrew the United States from the accord despite Iran’s verified compliance. His administration pursued a “maximum pressure” campaign of sanctions to coerce Tehran into a broader capitulation – not only on nuclear issues but on ballistic missiles and regional activities as well. The economic vise devastated Iran’s oil exports and currency, but it did not produce the intended diplomatic surrender. Instead, Iran retaliated in its own way: after a year of patience, it began breaching the nuclear deal’s limits in mid-2019, exactly as many analysts had warned. By the end of Trump’s term, Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium had grown and its enrichment level had inched upward – undoing key JCPOA achievements. Trump’s team also embraced a confrontational regional stance, openly backing Israel and Saudi Arabia in their anti-Iran alignment. In a move unprecedented in U.S. history, Trump designated Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a Foreign Terrorist Organization in 2019 (everycrsreport.com), citing its support for groups like Hezbollah, Hamas, and various Iraqi militias. The designation underscored Washington’s hardened view that Iran’s entire regional network was a terrorist enterprise. Tensions spiked dramatically in January 2020, when Trump ordered the drone strike killing IRGC-Quds Force commander General Qasem Soleimani during his visit to Baghdad. This assassination – of a figure considered Iran’s second most powerful man – brought the U.S. and Iran to the brink of open war. Tehran responded with missile strikes on U.S. bases in Iraq; mercifully, both sides then pulled back from further direct clashes.

The legacy of Trump’s policies has been double-edged. On one side, his pressure did succeed in inflicting long-term damage on Iran’s economy and curtailing resources that Iran could spend on proxies. It also signalled to Tehran that a future U.S. administration might not easily restore trust in any far-reaching deal, thereby perhaps deterring some Iranian escalation while he was in office. But the other side of the ledger is more evident today: Trump’s exit from the JCPOA unraveled constraints on Iran’s nuclear programme and led Tehran to accelerate enrichment. Many observers argue that the current nuclear crisis – with Iran much closer to weapons potential – is a crisis “of America’s own making” (americamagazine.org). Even some U.S. allies quietly lament that abandoning the deal squandered a historic opportunity to keep Iran’s ambitions in check. Trump’s maximalism also widened the gulf of mistrust. When President Biden took office in 2021 and sought to re-engage Iran, he found an Iranian leadership deeply sceptical of U.S. reliability. As of 2025, the United States finds itself militarily entangled again – deploying additional forces to the Gulf to deter Iran– and facing the prospect of either accepting Iran as a near-threshold nuclear state or contemplating military action to stop it. Neither outcome is palatable for Washington, illustrating the bind that Trump’s choices (combined with Iranian obstinacy) have created. For a British expatriate living in the UAE or Bahrain, the U.S.’s Iran policy is not an abstract debate but a tangible factor in local stability. American bases dot the Gulf, and when U.S.-Iran friction flares – as with the tit-for-tat strikes of recent years – those of us residing in these hub cities feel the jolt. Many expats recall the anxiety of January 2020, when missile sirens sounded on bases and speculation swirled about war. The U.S. may be an ocean away geographically, but its decisions reverberate powerfully through Middle Eastern expatriate enclaves, influencing everything from fuel prices to security alerts at international schools. As America now navigates the post-Trump aftermath, its challenge is to recalibrate a strategy that deters genuine threats without further fueling the cycle of escalation that imperils regional stability.

Saudi Arabia: A Rivalry at the Forefront

Few nations greeted Iran’s past cooperation with more cynicism, or its recent assertiveness with more alarm, than Saudi Arabia. The Sunni Arab kingdom and the revolutionary Shia Islamic Republic have been locked in a contest for regional primacy for decades – a rivalry often framed in sectarian terms but driven just as much by geopolitics and security dilemmas. Riyadh viewed the 2015 nuclear deal with suspicion, worrying it signalled a U.S. rapprochement with Iran that might embolden Tehran’s regional adventurism. Conversely, Saudi leaders quietly cheered the Trump administration’s abrogation of the JCPOA and its hardline posture. In the years since, Saudi Arabia has found itself on the front lines of confronting Iranian influence, sometimes at enormous cost. Nowhere is this more evident than in Yemen. Since 2015, Saudi forces have led a coalition intervention in Yemen’s civil war to defeat the Iran-backed Houthi rebels, who seized Sana’a and threatened to establish a hostile regime on Saudi’s southern border. The war became a quagmire and a humanitarian catastrophe, but Saudi Arabia felt it could not tolerate an Iranian proxy entrenched in Yemen. Iran, for its part, increased its support to the Houthis after 2015 – providing ballistic missiles, armed drones, and other weaponry that the Houthis soon turned against Saudi cities and oil facilities. By enabling repeated Houthi missile strikes on Riyadh, Jeddah, and Abu Dhabi, Tehran exacted a price for Saudi Arabia’s intervention. The Kingdom has also clashed indirectly with Iran in Syria (supporting opposition rebels against Assad while Iran backed Damascus) and in Lebanon (where Saudi once bankrolled factions to counter Hezbollah).

In recent times, Saudi Arabia has adopted a dual-track approach: hedging and hardening. Militarily and diplomatically, the Saudis have fortified an implicit alliance with Israel and the United States centered on containing Iran. This alignment became more public through the Abraham Accords of 2020, when key Gulf states like the UAE and Bahrain normalized relations with Israel – a move quietly blessed by Riyadh as part of a united front against Iran. Although Saudi Arabia itself stopped short of open diplomatic ties with Israel (pending progress on the Palestinian issue), security cooperation grew. Israeli and Gulf officials began sharing intelligence on Iranian threats, and talk of a potential Saudi-Israel-U.S. defense understanding gained traction in 2023. At the same time, Saudi Arabia showed a newfound willingness to explore diplomacy with Tehran under the right conditions. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, an architect of the Yemen war, surprised many by agreeing to China-brokered talks with Iran that led to the restoration of Saudi–Iran diplomatic relations in 2023 (atlanticcouncil.org). This détente was driven by pragmatic self-interest: the costly Yemen war needed winding down, and the Saudis calculated that reducing open hostilities with Iran could free their hand to focus on domestic economic transformation. The resulting rapprochement saw ambassadors exchanged and cautious optimism that proxy conflicts might cool. For a moment, it appeared that Saudi Arabia and Iran had found a modus vivendi, however limited. But events of 2024–25 severely tested this. As Israel’s undeclared war with Iran erupted, Saudi Arabia condemned Iranian “aggression” yet remained diplomatically reserved about Israel’s unilateral strikes. Riyadh clearly prefers not to see a nuclear-armed Iran, but it also fears the unpredictable consequences of a full-fledged Iran–Israel war on its doorstep – refugee flows, sectarian unrest, and economic shock. Thus Saudi Arabia today projects ambiguity: continuing to oppose Iran’s regional militancy (the Kingdom is still intercepting occasional Houthi missiles aimed its way), yet reluctant to be drawn into a direct military confrontation with Iran that could devastate Gulf stability. For British expats in Saudi Arabia or neighboring states, the Kingdom’s rivalry with Iran is often felt in subtle ways – from heightened security at oil compounds when tensions rise, to the subtext of news coverage and Friday sermons. There is a wary hope among expatriates and locals alike that Saudi Arabia’s recent diplomatic outreach will tame the rivalry’s worst excesses, because another era of outright proxy war (as seen in the 2010s) would bode ill for the region’s economic ambitions and social progress.

Qatar: Mediation from the Middle Ground

In the tapestry of Middle Eastern power politics, Qatar occupies a singular niche – a tiny but wealthy Gulf state that often punches above its weight through diplomacy. For Qatar, the tumult around Iran’s actions and the breakdown of law has presented both peril and opportunity. Doha maintains cordial relations with Tehran, even as it hosts vital American military assets and maintains ties with the West. This balancing act stems in part from geography and necessity: Qatar shares a massive offshore gas field (the North Field) with Iran, and during a Saudi-led blockade of Qatar in 2017–2021, Iran provided crucial airspace and supply routes to the Qataris. Those years taught Qatar the value of open lines to Iran. At the same time, Qatar is deeply integrated with Western security architecture – the Al Udeid Air Base outside Doha is the forward headquarters of U.S. Central Command and a key hub for operations in the region. How has Qatar reconciled these potentially conflicting affiliations? Largely by positioning itself as a neutral mediator in regional conflicts. Doha’s foreign policy elite have cultivated a role as go-betweens who can talk to all parties: Sunni and Shia, Islamist and secular, American and Iranian. Nowhere was this more evident than in the series of negotiations Qatar facilitated in recent years. Qatari diplomats were instrumental in brokering cease-fire deals during the 2023 Israel–Hamas war, leveraging Qatar’s relationship with Hamas (whose political leaders have long been based in Doha) and its working contacts with Israel and the U.S (livemint.com). When dozens of hostages were taken into Gaza in October 2023, it was Qatar that shuttled messages and eventually negotiated a humanitarian pause that saw some hostages and prisoners exchanged. Qatar’s mediating influence was acknowledged by all sides. Likewise, on the Iran–U.S. front, Qatar quietly helped facilitate indirect talks that led to prisoner swaps and discussions of interim nuclear arrangements in 2022 and 2023. By keeping Tehran’s trust, Qatar has been able to deliver messages and de-escalate situations that others could not – a valuable service as formal diplomacy falters.

Of course, Qatar’s approach has its detractors. Other Gulf Arabs, especially the UAE and previously Saudi Arabia, have at times viewed Doha’s coziness with groups like Hamas or the Taliban (which opened a political office in Doha) as dangerous freelancing that undercuts collective security. Indeed, one grievance of the Saudi/UAE-led blockade was Qatar’s independent streak in engaging Iran and Islamists. The United States, while appreciative of Qatar’s help mediating with Iran, remains wary of any Gulf state getting too close to Tehran. And Israel has a paradoxical relationship with Doha: on one hand, Qatar hosts a de facto Israeli trade office and has in the past funnelled aid money to Gaza in coordination with Israel; on the other hand, Israeli officials accuse Qatar of giving shelter and funds to Hamas. This delicate balance seemed to tip under pressure in late 2024, when reports emerged that Qatar, facing intense U.S. pressure after a protracted Gaza war, asked some Hamas leaders to leave its territory (eiu.com). Doha denied publicly it was expelling anyone, but the episode highlighted the fine line Qatar must walk. Ultimately, Qatar’s strategic bet is that dialogue and open channels serve its national interest better than confrontation. In an era of “might is right,” Qatar demurs, believing that smart power – talking to all sides – yields more durable outcomes. The wisdom of this can be seen in Qatar’s own stability: while other states in the region have been rocked by protests, attacks, or diplomatic crises, Qatar has generally managed to keep itself secure and economically booming (a fact not lost on the large expatriate community enjoying life in Doha’s glossy safe haven). For British expats in Qatar, the nation’s mediation role is often a point of pride – it enables Qatar to contribute to conflict resolution, which in turn helps ensure the kind of calm environment where business and cultural exchange (and high-end tourism) can flourish. Qatar’s challenge ahead will be maintaining this impartial stance if regional polarization grows. But if there is a glimmer of hope for negotiation in the Middle East today, it often travels through Doha’s corridors.

Israel: An Unyielding Adversary

To understand the current regional dynamic, one must grasp Israel’s pivotal role and its unyielding stance toward Iran. From Israel’s perspective, Iran’s nuclear programme and its patronage of anti-Israel militant groups are direct existential threats – challenges that cannot be managed by half-measures. This outlook has led Israel to pursue a strategy of confrontation and pre-emption vis-à-vis Iran, spanning covert action to open military strikes. For years, Israel was the chief critic of the Iran nuclear deal, arguing that the JCPOA’s sunset provisions and inspection protocols were insufficient to permanently bar Iran from the bomb. Israeli officials, notably Prime Minister Netanyahu, lobbied Washington intensively to abandon the deal, which dovetailed with the Trump administration’s inclinations. In parallel, Israel waged a clandestine shadow war against Iran’s nuclear and military assets. It is widely believed, for instance, that Israeli intelligence was behind a series of assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists and cyber-sabotage operations (such as the Stuxnet virus that disrupted Iranian centrifuges) during the 2010s. Israel also conducted hundreds of airstrikes in Syria during the last decade, targeting Iranian weapons convoys and bases to blunt Iran’s military entrenchment there. These actions, rarely officially acknowledged, were meant to enforce Israel’s red lines without triggering a full-scale war. However, as Iran’s nuclear work progressed and its proxies grew more active, Israel’s calculus hardened. By 2024, following the brutal Hamas attack from Gaza (which Israel attributed indirectly to Iran’s backing of Hamas), Israel shifted to more direct confrontation. The Israeli leadership made it abundantly clear that it would not tolerate an Iran on the threshold of nuclear arms. In a series of unprecedented moves, Israel prepared its military for long-range strikes and sought U.S. acquiescence for possible action. The moment of decision arrived mid-2025 when Israeli forces struck multiple targets inside Iran – from nuclear facilities to Revolutionary Guard sites – in a campaign that stunned the world. Israeli officials justified it as a “preventive” strike to forestall a nuclear-armed Iran, noting that intelligence did not show Iran had an active weapons but insisting one could be a mere heartbeat away (americamagazine.org).

The fallout of Israel’s bold strategy is complex. Tactically, the strikes set back Iran’s programme by destroying key infrastructure (early assessments suggested the attacks delayed Iran’s enrichment timeline by months, if not more) and dealt a blow to Iran’s prestigea==. The Israeli military demonstrated reach and precision, emboldening Israel’s hawks. Strategically, however, the operation carried huge risks. Iran did retaliate in limited fashion – firing salvos of missiles at Israel, some of which penetrated Israel’s multi-layered air defences and caused casualties. Hezbollah in Lebanon also escalated along the northern border, and skirmishes there forced mass evacuations of Israeli frontier towns (understandingwar.org). There was even worry that Israel might need to launch a ground incursion into south Lebanon to neutralize Hezbollah rockets. Regionally, Israel’s resort to force without broad international approval sent shockwaves. It “drove the final nail into the coffin” of the already ailing global order, according to some commentators, by proving that a state with sufficient might will act regardless of legal norms (eurasiareview.com). Inside Israel, the population and indeed many foreign nationals living there endured anxious weeks of air-raid sirens and uncertainty as the specter of multi-front war loomed. For Israelis and expatriates alike, 2025’s conflict with Iran was a stark reminder that the country remains in a perpetual security crisis, one that can erupt dramatically despite years of relative quiet. From a British expat’s lens, Israel’s actions, while perhaps understandable in light of its security doctrine, contribute to a regional volatility that complicates life for everyone. One may admire Israel’s determination to defend itself – no nation would sit idle under existential threat – yet also question whether military force can truly resolve what are fundamentally political conflicts. As Iran’s regime survived the initial onslaught and doubled down on its nuclear ambitions out of pride, it is unclear if Israel’s hard power move ultimately enhanced its security or simply pushed the inevitable diplomatic reckoning down the road. What is clear is that Israel remains utterly consistent: it will confront Iran as necessary, treaties and world opinion be damned. This consistency is a major reason the Middle East’s temperature stays high. Any long-term cooling will likely require addressing Israel’s core concerns (like stopping Iran’s path to a bomb) through robust agreements – something that seems distant at present.

Russia and China: Hesitant Giants in the Fray

Notably absent from direct intervention in these Middle Eastern dramas are the other great powers, Russia and China. Both have significant interests in the region and ties to its players, yet both have been reluctant – or simply too preoccupied – to involve themselves deeply in the latest crises. Russia, historically a heavyweight in Middle East politics (from Soviet times through its recent military role in Syria), finds its bandwidth severely constrained by the protracted war in Ukraine. Vladimir Putin’s government has condemned U.S. and Israeli actions against Iran in strong terms, positioning Moscow rhetorically as Tehran’s partner. Indeed, Russia’s relations with Iran have warmed considerably in the past few years. With Western sanctions isolating Moscow, the Kremlin has leaned on Tehran for drones and military supplies to use in Ukraine (apnews.com), forging what it calls a new era of strategic partnership. Yet when Israel and the United States struck Iran’s nuclear sites in 2025, Russia’s response was largely limited to outrage and diplomacy. Putin hosted Iran’s foreign minister in a show of solidarity, but there was no indication Russia would directly aid Iran militarily against Israel. Analysts note that Russia is overstretched – its forces and attention are tied down in Europe, and it can ill afford a confrontation with Israel or the U.S. in the Mideast. Moreover, Russia’s regional clout has been dented. Its intervention in Syria (starting 2015) once made it a power-broker, but with Syria’s civil war outcome essentially set (and reports that Damascus’s regime even faltered in mid-2025, possibly falling), Moscow’s leverage diminished. Its failure to prevent the recent collapse of the Assad regime (a key Russian ally) has, in the eyes of some, revealed the limits of Russian influence in Middle Eastern affairs. Consequently, Russia has contented itself with diplomatic maneuvering: offering to host conflict talks, casting vetoes or proposing resolutions at the UN to shield Iran, but stopping short of any direct confrontation. In essence, Russia today acts as a sympathetic bystander – supportive of Iran’s positions and happy to fan anti-Western sentiment, yet unwilling (and perhaps unable) to materially alter the course of events on the ground.

China, by contrast, wields growing economic influence in the Middle East but has remained diplomatically cautious. Beijing’s interest in the region is primarily driven by energy security and its global Belt and Road infrastructure initiative. China has cultivated good relations with Iran (a major oil supplier) and with Arab states and Israel alike, taking pains to avoid being caught in others’ fights. In a dramatic diplomatic coup, China brokered the reconciliation between Saudi Arabia and Iran in March 2023, heralding what some called a “post-American” regional order in the Gulf (atlanticcouncil.org). That achievement showcased Beijing’s potential as a peace-broker: it succeeded where Western powers could not, largely because China could speak to both sides without ideological baggage. However, beyond facilitating dialogue, China remains reluctant to entangle itself in Middle Eastern conflicts. Chinese officials consistently call for “restraint” and “respect for sovereignty” in regional disputes – a thinly veiled critique of Western interventions – but they do not marshal coalitions or deploy forces to uphold those principles. In the Iran-Israel saga, China has condemned violations of international law in general terms and urged a return to negotiations, aligning with its global stance of non-interference and preference for stability. Yet Beijing has also been careful not to damage its relations with Israel or the U.S.; it has not, for example, moved to breach U.S. sanctions on Iran in any large-scale way (though Chinese companies do buy Iranian oil with some subterfuge). Simply put, China’s strategy is to keep a low profile militarily while expanding economically. The Middle East is too strategic to ignore, but too volatile to wade into directly. For China, the ideal outcome is a stable region where great-power competition is minimal and business can flow – hence its championing of détente like the Riyadh-Tehran accord. But in a scenario of heightened conflict, China is likely to stay on the sidelines, perhaps offering mediation but certainly avoiding choosing a definitive side.

From the perspective of those of us living and working in the Middle East, Russia and China’s semi-absence is a mixed blessing. On one hand, their non-intervention means fewer cooks in an already messy kitchen; the last thing the region needs is Cold War-style proxy showdowns or an arms race fueled by rival superpowers. On the other hand, their hesitancy also underscores a vacuum of effective great-power stewardship. For all the criticism of U.S. overreach, Washington at least used to invest diplomatic capital in tamping down Middle East crises (or, arguably, in not letting them spiral out of control). With America’s focus wavering, and Moscow and Beijing largely self-interested or distracted, there is a sense that local actors are more “on their own” than at any time in recent memory. Some Gulf commentators speak of a new multipolar reality where no outside power will put out the fires – a reality that pushes regional players either to find accommodations or to double down on raw power, each for himself. As expatriates in the Gulf and Asia, we prefer the former path for obvious reasons. The stability and prosperity of our host countries have benefited historically from a relatively rules-based, U.S.-anchored order. A retreat to pure might-makes-right between regional rivals creates uncertainty that can quickly affect expat life – whether through sudden security threats, economic downturns, or social tensions. Thus, while Russia and China sit out the fray for now, one cannot help but wonder: if not them, who will step up to champion international norms or mediate compromises? The worry is that no one will – and that truly heralds a more dangerous world for all.

BA Conclusion: Increasingly Complexity Requires Nuance

Standing back and surveying these complex, contradictory realities, one is struck by how far the Middle East has diverged from the hopeful narratives of the late 20th century.

In place of steady progress toward peace and international integration, we see a region where both Iran’s past constructive compliance and its recent disruptive behavior coexist; where international law lies tattered under the boots of powerful states; and where diplomacy flickers as a faint candle in a tempest of militarism. For a British expatriate community spread across hubs from Dubai to Singapore, this state of affairs is disquieting. Many of us came of age in an era when diplomacy and law – often championed by Britain and its allies – were considered the first resort in global affairs. We remember the painstaking negotiations that ended conflicts in Northern Ireland or the Balkans, and we instinctively view dialogue as the proper path. To witness the Middle East seemingly give up on that ideal, reverting to an order determined by drones and missiles, is deeply concerning. It affects us not only morally but practically: regional instability endangers the economic growth and personal safety that expats and locals alike depend on. When oil facilities are attacked, when shipping lanes are threatened, when embassies are stormed, it is not just headlines on a distant shore – it’s our friends’ workplaces, our travel routes, sometimes our homes that are at risk.

And yet, even in this troubled landscape, one must take a longer, balanced view. Iran’s story itself shows the capacity for change and the importance of keeping nuanced perspectives. Here is a nation that, within the span of a few years, demonstrated total adherence to a nuclear pact and then, faced with broken promises, pivoted to defiance and ultranationalist fervor. Both phases were driven by Iran’s perception of how it was treated by the world’s powers. This suggests that how we handle Iran (or any other state) can indeed influence its behavior over time. Squeezing an adversary into a corner may breed short-term concessions, but it often nurtures long-term rebellion – a pattern evident in Iran’s case. Conversely, offering respect and avenues for legitimate progress may not guarantee goodwill, but it lays a foundation that pure coercion cannot. For the international community, especially Western powers and the regional actors we have discussed, the task now is to somehow revive that foundation. Admittedly, with missiles flying and rhetoric venomous, it is fantastically difficult to imagine Iranian, Israeli, Saudi, and American officials all returning to serious negotiations. But history has a way of confounding pessimists. A decade ago, few believed the U.S. and Iran could find common ground – until quiet talks in Oman led to the JCPOA framework. Similarly, Saudi Arabia and Iran were arch-enemies until China’s mediation proved otherwise. These examples should remind us that diplomacy is the art of the possible. The current deterioration of international norms need not be permanent if enough leaders and peoples come to recognize that the alternative – a lawless free-for-all – threatens everyone’s quality of life.

For British expats in particular, with our unique vantage point and often a foot in both East and West, there is an opportunity to act as informal bridge-builders. In our professional roles – be it in finance, education, engineering, or journalism – and in everyday interactions, we carry the values of dialogue, fairness, and rule of law that are the best of Britain’s heritage. Living in Southeast Asia or the Middle East, we also gain an appreciation of local perspectives and grievances that outsiders sometimes overlook. By fostering understanding in our micro-environments and refusing to indulge in sensationalism or zero-sum thinking, we contribute in our small way to a climate more conducive to compromise. It is a subtle influence, to be sure, but not a trivial one. After all, the late 20th-century British approach to global affairs, which this article has tried to emulate in style – measured, analytically rigorous, eschewing hysterics – is itself a reminder that clear-eyed pragmatism can prevail over bombast.

In closing, the Middle East stands at a perilous juncture where two truths run in parallel: that Iran once showed it could be a responsible stakeholder and now proves a disruptive force; that world leaders speak of law and peace even as they prepare for war. Acknowledging these contradictions is the first step to resolving them. The region’s future will depend on recoupling power with principle – finding a settlement on Iran’s nuclear programme that all sides can live with, reining in proxy conflicts through regional security dialogues, and reasserting that even superpowers must obey some rules. The road to that future is hard to discern through the smoke of recent battles. But for those of us who have chosen to make our lives abroad in this dynamic yet challenging part of the world, giving in to cynicism is not an option.

We have a stake in a stable, lawful Middle East – a region where might does not unilaterally make right, and where a negotiated balance allows all to prosper. It may be a distant prospect, but it remains a vision worth striving for, through all the setbacks and contradictions along the way.